BLOG

BLOG

OAuth has become a highly influential protocol in the past few years due to its quick and wide adoption in the industry. The protocol was started to fulfill websites' authorization needs, but it has become more than that over the years.

Over the years, the protocol has been significantly repurposed and re-targeted, especially now for mobile platforms other than the web. While it has picked up pace and adoption, it has also become a target for hackers precisely because of the same reason and because most developers do not implement it correctly. Let's delve deeper into this protocol and understand why this is both a boon and a bane.

OAuth is an open standard initially envisioned by the developers behind Twitter’s OpenID. Since then, it has gained rapid adoption across many websites, including Facebook, Google, LinkedIn, and more. It is widely used in various web and mobile applications, especially to provide mechanisms for user authentication. This has led many developers and API providers to believe that OAuth is an authentication protocol. It is not.

Most of this confusion is caused by the fact that OAuth is used inside authentication protocols. Developers see the OAuth components and interact with their flow, and they often assume that simply using OAuth can result in user authentication. This is not only untrue but also very dangerous for businesses and users.

A paper written by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University explains this very well. Originally, OAuth was designed to provide a secure authorization mechanism for websites. It defines a process for end-users to grant a third-party website access to their private resources stored on a service provider. The third-party website is often called the consumer, client, or relying party, and the word "relying party" is often used.

There are two versions of the OAuth protocol: OAuth 1.0 and OAuth 2.0. Real-world websites actively use both. Ever since the industry successfully adopted OAuth, major companies have repurposed it for authentication.

The protocol enables a user to prove his or her identity to a relying party by utilizing his or her existing session with the service provider. The web industry’s trend toward obsolete other protocols and moving toward OAuth is decisive—the new authentication mechanisms provided by the companies mentioned above are all OAuth-based.

Therefore, even though neither OAuth 1.0 nor OAuth 2.0 documentation explicitly focuses on authentication, OAuth is now a de facto authentication and authorization protocol.

The OAuth website gives a simple metaphor to help you understand this - chocolate vs. fudge. Basically, the nature of both is different - chocolate is an ingredient, and fudge is a confection. Chocolate can be used to make many different things, and it can even be used on its own. Fudge can be made out of many different things, and one of those things might be chocolate, but it takes more than one ingredient to make fudge happen, and it might not even involve chocolate. As such, it's incorrect to say that chocolate equals fudge, and it's certainly overreaching to say that chocolate equals chocolate fudge.

Related Topic- Understanding OWASP Top 10 Mobile: Poor Authorization and Authentication

OAuth, in this metaphor, is chocolate. It's a versatile ingredient that is fundamental to a number of different things and can even be used on its own to great effect. Authentication is more like fudge. There are at least a few ingredients that must be brought together in the right way to make it work, and OAuth can be one of these ingredients (perhaps the main ingredient) but it doesn't have to be involved at all. You need a recipe that says what to combine and how to combine them, and many different recipes say how that can be accomplished.

Like their web counterparts, mobile applications need authentication and authorization. After gaining popular adoption in the web space, OAuth became the obvious choice in the mobile space. According to a study, more than 24% of the 600 top Android applications in several Google Play categories use OAuth.

So, what's the big deal, you ask?

Using OAuth for mobile has some security concerns, as this protocol was primarily designed for traditional web technology and not for mobile platforms. Hence, educating mobile application developers about this becomes even more important. Despite its wide usage, the OAuth protocol is quite complicated for average developers to comprehend and handle.

Here's an example of its complexity: The security property of the OAuth access token differs between OAuth 1.0 and 2.0. In OAuth 1.0, each access token is bound to and can only be used by the relying party to which it was issued. However, an access token in OAuth 2.0 (also referred to as a “bearer token”) can be used by any party in possession of it.

Must Read: 3 Basic Mobile Security Principles that Every App Developer Should Be Aware of

The diversity of mobile applications is the real cause of issues with OAuth in mobile platforms. Not only is the protocol defined in multiple specifications with two different use cases, but its mobile usage is also poorly defined and underspecified. This is why developers are often forced to create their own interpretations, most of which are bad from a security point of view.

Before OAuth was launched, another popular OenID protocol existed for third-party user authentication. OpenID had an issue: secure API access delegation. In simple words, this means authorization, and hence, OAuth was designed to address this problem of authorization mainly.

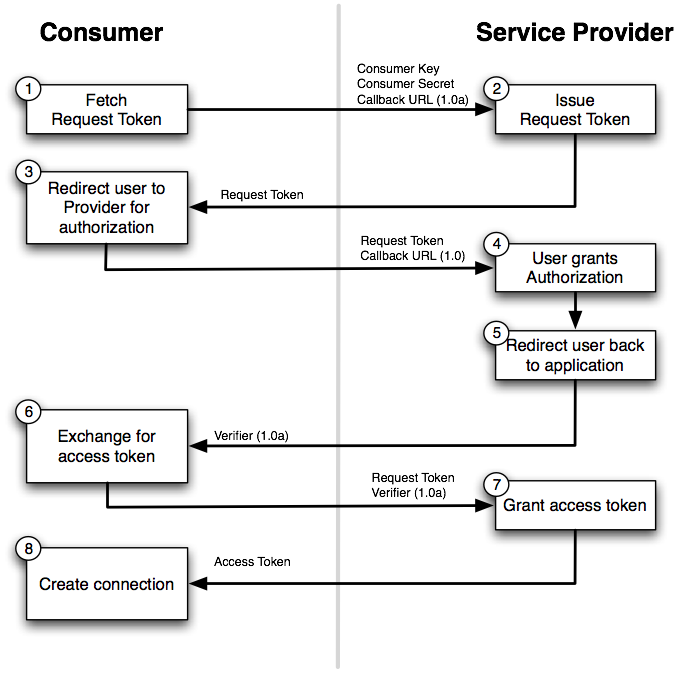

Here's a diagrammatic representation of the connection flow in the case of OAuth 1.0 and OAuth 2.0

OAuth 1.0 Connection Workflow

OAuth 1.0 Connection Workflow

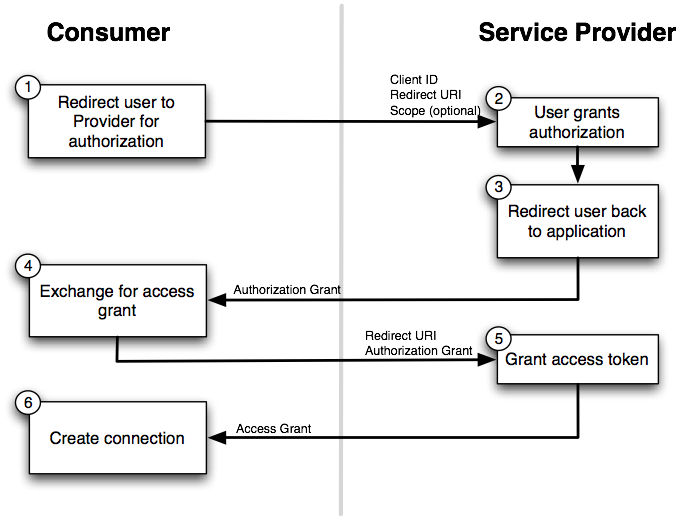

OAuth 1.0 had several notable limitations for its usage scenarios. However, instead of augmenting the existing protocol, the working group altered the specification entirely to create a different protocol – OAuth 2.0.

OAuth 2.0 introduced a significant change: the concept of bearer tokens. A user’s access token was no longer bound to a relying party; any party possessing this token could freely access the user’s protected resource.

Authentication usually occurs before an access token is issued. Developers are often tempted to consider the reception of an access token proof of authentication. However, just possessing an access token doesn't tell the client API anything by itself. For true authentication to occur, the client should be able to get some information from the token, which doesn't happen in the case of OAuth. In the case of OAuth, the client is the authorized presenter of the token, and the audience is, in fact, the protected resource.

A common issue is that developers fail to understand the purpose of relying upon party secrets and storing them locally inside the client application.

Researchers believe that the terminology of OAuth confuses developers significantly – the relying party secret is referred to as the “consumer secret” by OAuth 1.0 and “client secret” by OAuth 2.0, where each specification uses the terms consumer and client to describe the relying party.

These names are misleading for developers who have never studied the specifications, which is most of them. These names are extremely misleading for developers who have never studied the specifications.

Here's a real-life example:

The research paper written by Eric Chen et al. highlights a real-world example of Pinterest and Quora.

Both Pinterest and Quora used Twitter as a service provider for authentication, and both of them bundled their relying party secrets with their mobile applications. To make the matter worse, after obtaining their secrets using simple reverse engineering, we discovered that the same secrets were used for the Pinterest and the Quora web applications. Since Twitter mainly used OAuth 1.0, this gave an adversary the ability to generate arbitrary OAuth request tokens for Quora and Pinterest. Using these tokens, we (acting as the attacker) could direct users (both web and mobile users) to a legitimate Twitter page with the dialogue box. Once the user clicks authorize, Twitter’s access token will be sent to the attacker, giving him/her full access to the user’s account.

Here's another perilous security threat as far as OAuth implementation is concerned. This is where a client accepts access tokens from sources other than the return call from the token endpoint. This can occur for a client that uses the implicit flow (where the token is passed directly as a parameter in the URL hash) and doesn't properly use the OAuth parameter.state

This is problematic because it opens up a place for access tokens to potentially be injected into an application by an outside party (and potentially leak outside of the application). If the client application does not validate the access token through some mechanism, it cannot differentiate between a valid token and an attack token.

This is a problem because it opens up a place for access tokens to potentially be injected into an application by an outside party (and potentially leak outside of the application). If the client application does not validate the access token through some mechanism, there is no way of differentiating between a valid token and an attack token.

So, how do you solve this? This can be solved by using the authorization code flow and only accepting tokens directly from the authorization server's token endpoint and by using a state value that is unguessable by an attacker.

Since the OAuth specification does not specify how to perform user-agent redirection for mobile applications, it may seem natural to use a mobile browser or an embedded browser (i.e., WebView) to perform web-based OAuth redirections on mobile devices.

Again, an issue that is highlighted in the research paper by CMU is as follows:

WebView is common for service providers that utilize a single protocol flow for web and mobile relying parties. Many notable service providers, including Twitter, Microsoft LiveID, Flikr, and Renren, fall into this category.

Unlike Facebook and Google, these service providers do not facilitate OAuth flows for the mobile-relying parties using their own mobile applications. Instead, they use their websites to conduct all mobile OAuth transactions.

Many mobile developers natıvely believe that since the OAuth specification is specifically designed for web usage, one can securely apply it to mobile platforms by using the web-based flow inside a mobile web browser (or a WebView instance). This is a common misconception, as we have not found a case in our study where a mobile browser or WebView is used securely for OAuth.

Everything moves to social and mobile, including integrations with Facebook and similar social websites. With smartphones' growing usage, businesses and users want quick access to services and systems. OAUth is a great way to achieve that, but as we mentioned above, it is essential to implement it correctly. Otherwise, it can be a pain for your business and users.

.jpg?width=50&height=50&name=10606600_10204086667262761_7381430219125488912_n%20(1).jpg)